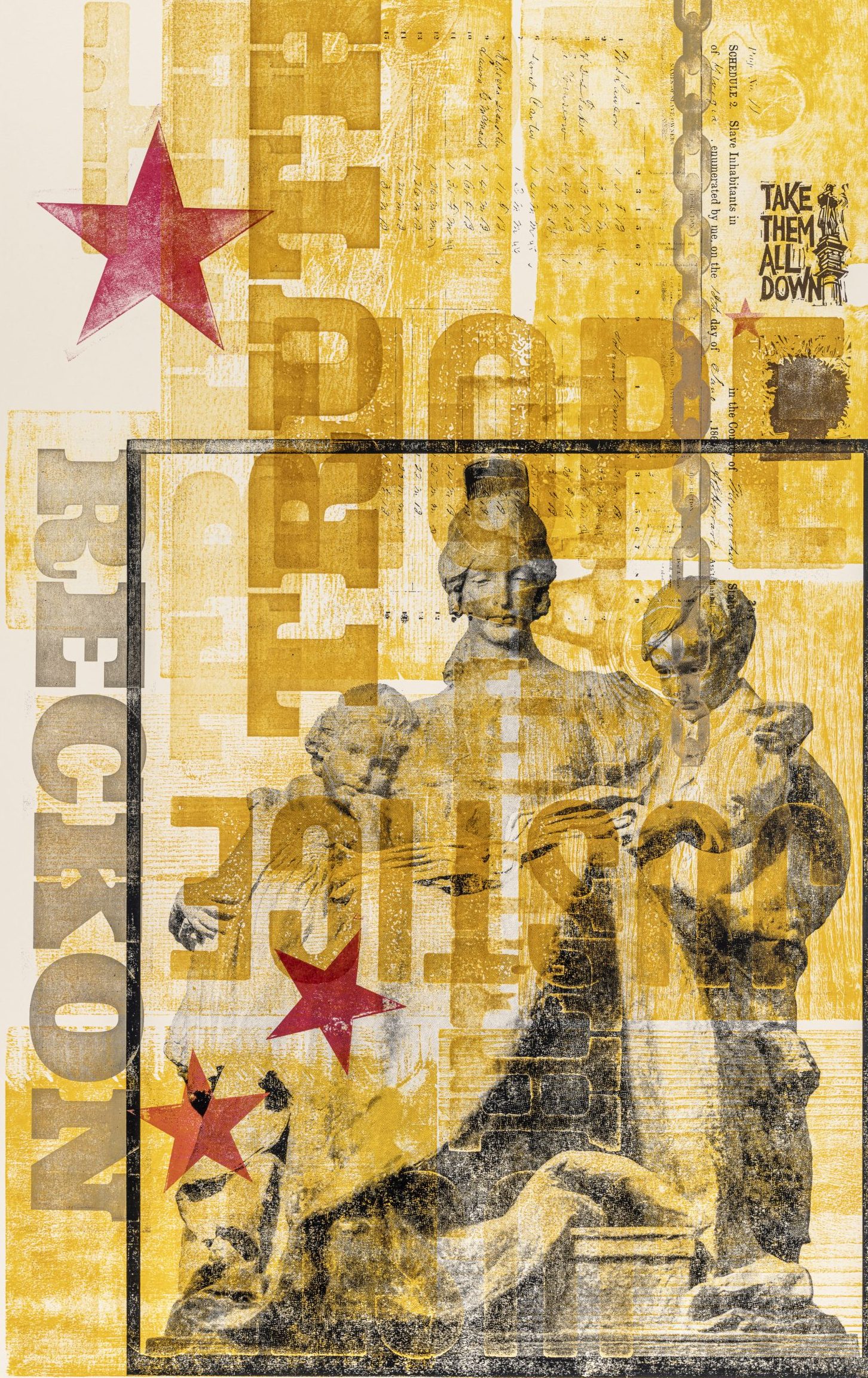

“The symbol of the Woman of the Southland is pervasive in our culture. As the mother and daughter of the confederacy, she appears in books, films, and public spaces for generations. Her antebellum dress, the lilt in her voice, and her projected purity and graciousness have given her a vaulted position in our nation’s narrative. Yet, as a symbol, and in many cases as a real person, she is heinous.

In the movement to remove confederate monuments from the public landscape, she has been the most tenacious and sticky of objects. “But she is so beautiful.” “She is just a woman reading to her children.” “It was put there to honor their sacrifices as their sons and husbands went off to war.” “She is doing no harm.” “Maybe we can just pretend she represents all women of the south.” These are just a few of the responses provided by those who disagreed with her removal from Springfield Park in December of 2023.

But the historic record says otherwise. She was installed as part of the ‘lost cause’ narrative when the sons and daughters of the confederacy erected monuments and rewrote text books in communities throughout the country to scrub clean the stench of racism and violence perpetuated in the effort to preserve slavery and to remind Black citizens that Reconstruction was over and that they needed to renew their subservient position.

Even after the schools named for confederate oppressors changed, and the insurrectionist soldier was removed from what is now James Weldon Johnson Park was removed, the Woman of the Southland continued to be defended and protected. It is one of hundreds of examples across time and place of white women, especially those of the gentile “bless your heart” class, being protected at the demise of Black lives.“.

These words are excerpt from the text that accompanied the exhibition ‘Legacy Interrupted: Recent Works by Hope McMath’ which was on view at Yellow House earlier this year.